In 1967, Jocelyn Bell, a graduate student at Cambridge University, made a startling discovery. While analyzing radio telescope data, she detected a series of ultra-precise, rhythmic pulses from a distant cosmic source. Initially puzzled, Bell and her supervisor, Antony Hewish, dubbed the signal "LGM-1," for "Little Green Men." This half-jokingly suggested the uncanny regularity might be a beacon from extraterrestrial intelligence. Further investigation revealed the source was a rapidly rotating neutron star, later called a pulsar, emitting radiation beams like a cosmic lighthouse. Bell’s discovery of the first pulsar revolutionized astrophysics, paving the way for the later discovery of black holes, and briefly sparked speculation that humanity had detected evidence of intelligent life elsewhere in the universe.

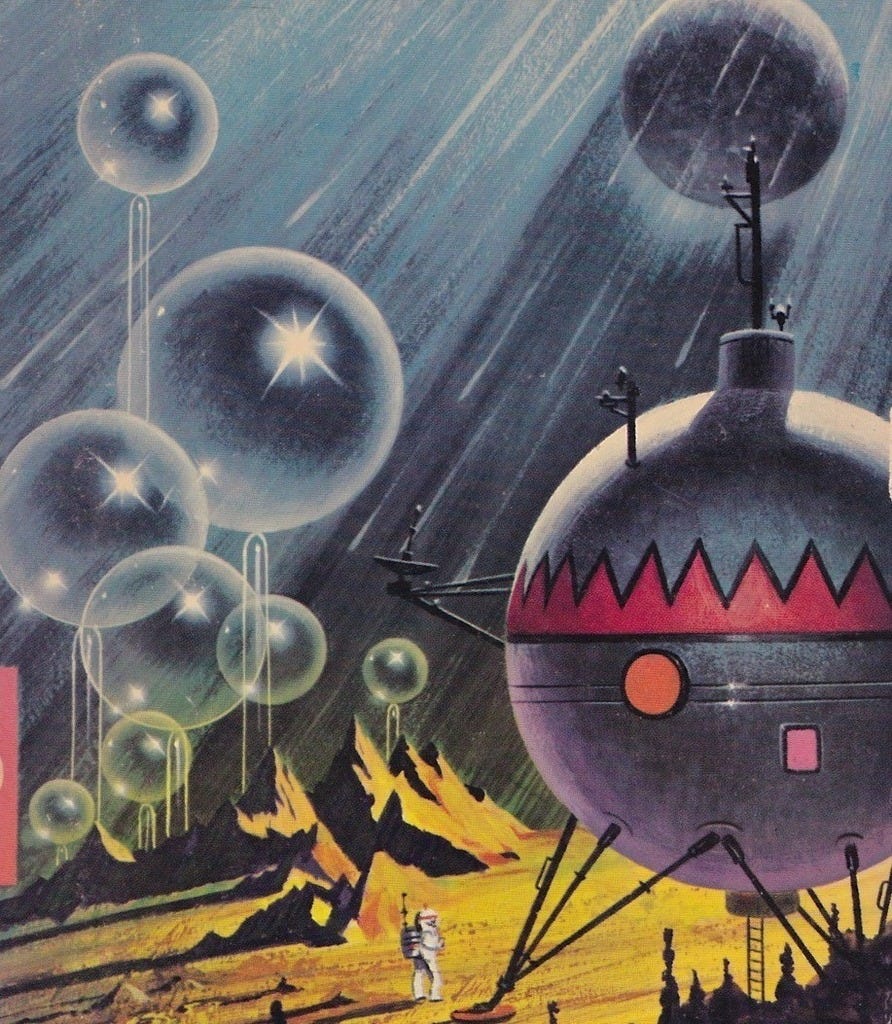

This wasn’t the first time people got excited about the possibility of not being alone. In 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiapparelli, while observing Mars, sketched features he labeled ‘canali,’ the Italian word for channels. Mistranslated into English as "canals," the term fueled speculation about the Martian engineers who built them. Though no evidence supported this, the excitement persisted well into the 20th century, inspiring works like H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds and C.S. Lewis’ Out of the Silent Planet.

Since 1967, periodic news reports have claimed discoveries of habitable Earth-like planets or evidence of microbial life elsewhere in the Solar System. Whether substantiated or not, these reports raise questions about whether extraterrestrial life conflicts with the Christian view of creation.

Let’s pause for a thought experiment. If you were presented with undeniable evidence of extraterrestrials, how would it affect your beliefs? Does your worldview already lean toward the likelihood of extraterrestrial intelligences (ETIs)? Or would it challenge your belief that life is exclusive to Earth?

For Christians, a key question is whether life—especially intelligent life—is unique to Earth. When I emerged from the atheism I was raised with and began to study theology, I started with the ancient and medieval Jewish Torah scholars. I was surprised to learn they believed the universe was created with the potential for life built into it, not just on Earth but throughout. This aligns with the scientific evidence showing the universe is exquisitely fine-tuned for life. From both the biblical and the scientific perspective, I’d be surprised if we didn’t eventually find evidence of basic life forms elsewhere.

The religiously significant question is not whether we’ll find some microbes on another body in the universe, but whether we’ll find intelligent or conscious life elsewhere. The biblical view suggests these would be deliberate acts of God, not natural outcomes of universal processes. In The Science of God, physicist and theologian Gerald Schroeder notes that Genesis uses two distinct Hebrew verbs: “created” (bara) and “made” (asah). Bara (created) denotes an instantaneous act of bringing something into existence from nothing, and is used only three times in Genesis: for the creation of the universe on day one, for the creation of animal (intelligent) life on day five, and for God breathing a soul into Adam’s body on day six. These are biblically miraculous events for which science currently has no explanation. For other events, including the appearance of plant life on day three, asah (made) is used, implying the restructuring of existing material. Non-intelligent life, like hypothetical bacteria on Mars or an asteroid, would fall under “made.” Intelligent, conscious life would be “created.”

Would the discovery of conscious beings elsewhere undermine the biblical view of creation? It would only if Genesis claimed Adam’s creation was a singular, unrepeatable event. Yet, nothing in scripture, to my knowledge, suggests this. The Bible focuses its narrative solely on life on Earth and its relationship with the Creator. This leaves open the possibility of other conscious beings with whom God has a relationship. C.S. Lewis, the renowned Christian apologist, explored this in The Space Trilogy, depicting humans encountering unfallen alien beings on other planets who enjoy direct communion with God.

Rev. Dr. Joel D. Heck1, summarizing Lewis’ views in his essay, “Religion and Rocketry,” notes:

In Paul’s letter to the Romans (8:19–23), Lewis argued, God hints that the longing for redemption is cosmic, and therefore not limited to this world. Perhaps redemption has happened for all those who need it, has happened through Christ’s redemption, and has somehow been extended to other creatures. But we really don’t know. And to speculate about other creatures in other worlds takes us into the imaginative narrative that comprises Lewis’s [Space] Trilogy, especially Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandra. One paragraph of the essay in particular, beginning with the words “It is interesting to wonder…,” imagines the scenario that Lewis spells out in Out of the Silent Planet. We find Lewis speculating that the vast distances in the universe are “God’s quarantine precautions,” designed to prevent the rest of the universe from being contaminated by the corruption of our world.

This perspective suggests a humbling possibility: the 39,900,000,000,000 kilometers to our nearest stellar neighbor (Proxima Centauri) might be God’s way of shielding other worlds from the equivalent of spiritual human measles. While unsettling, it’s a plausible explanation for the vastness of space.

Lewis’ imaginative framework opens the door to various possibilities for ETIs and their relationship with God, including:

They’re unfallen and need no savior.

They’re fallen and offered redemption through Jesus Christ, as we are.

They’re fallen and offered a different path to redemption.

They’re fallen and not offered redemption.

A challenge for the materialist view that humans lack a spiritual component is explaining why 90% of humanity across history has exhibited a sense of or deep longing for the spiritual. Secular explanations often dismiss this as an evolutionary byproduct. So let’s use this to turn the tables. What if we discovered ETIs, communicated with them, and found they’re as spiritually inclined as humans? Would this undermine materialism? It seems so, given the immense improbability of two distinct species in separate corners of the universe independently developing the same “evolutionary tic.”

The existence of extraterrestrial life, intelligent or otherwise, doesn’t inherently conflict with the biblical worldview. Instead, it invites us to ponder the possibilities of God’s relationship with other life while challenging the materialist perspective on spirituality.

This article is an expanded and edited version of an article from my old blog.

Related: Earth-like planet kills God dead (my old blog)

Note to would-be critics in the comments: If you don’t agree with my points and you want to talk about it, let’s chat. If you have questions, ask away. But there’s a good chance I’ve already addressed your questions and criticisms here—please read it before you engage.

If you liked this article, do me a favor and hit the like button below—it helps me know what resonates with readers and it boosts my writing. There’s also a share button if you want to send it to a friend who’d enjoy the science-and-faith conversation. If you’re a free subscriber who would like to support my ministry, you can upgrade to a paid subscription (which comes with some perks!).

“Reverend Heck” sounds like the polite, midwestern version of a graphic novel villain.

I'm confidently and eagerly expecting the discovery of, at a bare minimum, plant life in Europa, Callisto, and Enceladus.

Another fictional account of intelligent life on other planets and their need for the gospel is Michel Faber's novel The Book of Strange New Things. I didn't read but my wife did and she says it was extremely interesting and thought-provoking; it concerns a missionary who travels to a distant planet and evangelizes the native population while dealing with troubling happenings in his relationships back on earth.

Love your content! As an English teacher I need to be that guy.

Just before your Rev. Heck quote you write, "C.S. Lewis, the renowned Christian apologist, explored this..." and right after that mention "The Space Trilogy." There should either be punctuation completing the sentence or, more likely, a preposition linking it to the title of the book. I think you probably meant to put "in" in there, but I'm just guessing.

Thanks, love your stuff. Congrats on moving up the Substack ranks!!