I was born in Oregon, but my socialist, atheist parents moved us up to Canada when I was very little. That’s where I grew up, and for a long time it was like home. But I left Canada in my mid-twenties, because I wanted to live in the United States, where I thought I would be freer.

When I returned to the U.S., I was not a socialist like my parents had been at that age, but I was still an atheist. I had become a follower of Ayn Rand’s Objectivist philosophy and believed in personal freedom as the ultimate good, but I didn't believe God or religion were necessary for that. In fact, to me, those things seemed antithetical to freedom.

But within a few years, I grudgingly came to realize that Christianity is a necessary part of what it is that makes the U.S. unique and the sort of place that attracts millions of people from around the world. If you’re interested in that topic, I recommend Dinesh D’Souza’s books, What’s So Great About America and What’s So Great About Christianity.

The basis for freedom is the importance of the individual. I believed in individual rights. I believed in the uniqueness and value of every single person on the planet. My atheism began to crumble when I realized the only rational, consistent basis for those things was Christianity.

The problem with individualism, however, is that the great moral good that comes from recognizing the value and rights of individuals—and I do believe in those—can be distorted and fetishized into hyper-individualism.

When I became deeply skeptical of socialism at a young age, I turned instead to what I thought was its opposite in (small l) libertarianism. I read libertarian books, like Ayn Rand’s fictional manifestos to personal liberty, and Harry Browne’s How I Found Freedom in an Unfree World. But something seemed off about them to me. For all Rand’s fixation on personal happiness, she came across as terminally unhappy. And Browne was so devoted to the ideal of personal freedom that his book seemed more like a treatise on how to be as isolated and unlikeable as possible. It was all focused on the liberty of the individual over anything else, including ties of friendship, family, and community. No wonder people like this can’t get it together in the political arena—disconnection is baked into the philosophy.

I’ve lately come to realize that while the sanctity of the individual is a moral good, hyper-individualism is not, and that is the direction we’re headed the more we abandon the Christian basis of our culture. As paradoxical as it seems, Christianity is both the basis for individual rights and the means by which a society is prevented from descending into hyper-individualism.

I realized all this today as I watched a show about the death of the movie theater, which I find both very sad and a portent of not-good things to come.

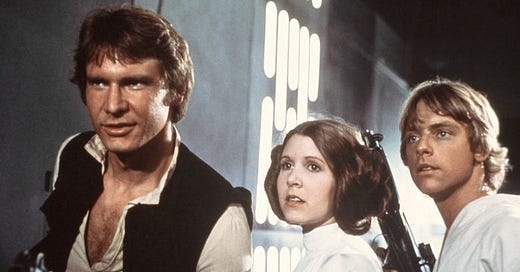

The reason this interests me is that I love movies. I mean, I love movies. I went to all the movies as a kid. I saw every Star Wars and Indiana Jones movie over and over in the theater when they came out. I worked at video stores in high school and in my twenties just so I could be around movies. I didn’t have a car in college, so every week I walked to the downtown theater to spend my last dollar on a movie. I trudged through winter storms in eastern Oregon to watch Galaxy Quest and Toy Story 2. I was the first in line to see Gladiator. When I worked summers on the UC-San Diego campus, I walked a mile uphill both ways (seriously) to watch every single new release that came out that summer. When The Phantom Menace came out, I found someone to drive me an hour away to see it at the only theater in eastern Oregon that was playing it early.

Believe me when I say, I love going to the movies.

Now, guess how many movies I saw in the theater last year?

Two: Barbie and Oppenheimer, both on the same day.

Number of times I’ve been to the movies so far this year: one (Dune 2).

I hardly go to movies anymore, because for me the experience is almost completely dead. Movies are mostly boring, bloated, preachy, politically correct, and uninspired. Actors and filmmakers have destroyed all sense of mystique by being themselves on social media. Covid shutdowns broke the moviegoing habit for a lot of people, including me. And we all know that anything in the theater will be on streaming apps within a few weeks anyway, so why spend $50 just to see it in a stuffy theater with people who are constantly checking their phones?

I sense that those in the industry are starting to realize how precarious the situation is, which is why we’re once again getting ostensible crowd-pleasers like The Fall Guy and Furiosa. Those movies actually looked good and probably would’ve been box office successes a few years ago, but they flopped in theaters. Personally, I just couldn’t get past my mildly annoyed apathy to go see them, especially when they're going to be on Hulu or Max soon anyway. It’s not clear how much longer this can go on before most movie theaters become a thing of the past.

Okay, so what’s all this got to do with the problem of hyper-individualism?

For a long time, movies were a shared experience for Americans. Along with popular music, movies were a major contribution to a shared culture. We’d ask friends, coworkers, even strangers, “Did you see the new [whatever] movie? What did you think of it?” We all mostly loved the same movies, the same stars, the same soundtracks. Even if you disagreed with someone politically, you could be united by your love for the same movies. Remember quoting famous lines to people? Remember relating to each other through movie metaphors? You could be a Republican and the guy you worked with could be a Democrat, but you connected over your love of James Bond or Star Wars or Indiana Jones.

With the decline of the moviegoing experience and the advent of countless streaming choices, we’re literally fragmenting into a million subcultures each with its own niche tastes. How can you connect with that politically-opposite person when you each have your own highly-cultivated forms of entertainment? We’re not only losing a shared cultural context, we’re losing opportunities to connect with people on a deeper level. If you’ve ever been in a theater for an “event” type movie, you know that special joy you feel when you’re all unified by the experience.

There are even studies showing that gathering in large groups to experience an event increases synchronization of brain waves of the participants. Going to the movies is in every sense a shared experience.

I don’t know if anything is going to fix the pop entertainment problem. Mass forms of entertainment have been around for thousands of years, but maybe they can’t contend with the combined forces of political correctness and the internet. And without a popular culture to unite us, we’re fragmenting more and more into lonely, depressed, anxious little islands of humanity consuming our ultra-niche, cultivated, bespoke forms of entertainment.

This is where Christianity provides a permanent fix to the problem of hyper-individualism. Now, it must be pointed out that I am Christian, not because I believe it’s expedient to be one, but because I believe it’s true. Nevertheless, Christianity, like every major religion, has a practical purpose in uniting people. Where Christianity stands out from all other religions is its power in unifying, not just people who are alike, but every kind of person:

…for in Christ Jesus you are all sons of God, through faith. For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. And if you are Christ's, then you are Abraham's offspring, heirs according to promise. —Galatians 3:26-28

Isn’t it amazing?

But there is balance in everything. To the degree that we are connected, we are also obligated to each other. That means communal worship, fellowship, helping those in need, being there for others even when you don’t feel like it, sometimes to the point of inconvenience and pain. Getting up early on a Sunday when you’re tired may seem like an annoyance at times, but when you go and worship with dozens to thousands of other people, you’re contributing to and benefiting from one of the most shared experiences possible. With apologies to Harry Browne, there is no real happiness apart from obligation to others.

If you’re a devoted Christian, you’re already part of this unifying culture. If you’re wavering in your faith, or thinking of becoming Christian, consider the unique benefit of knowing that you’re a custom, one-of-a-kind creation, loved by God more than you can imagine, created with inherent worth and individual rights, but also part of a vast tight-knit family with a shared narrative that encompasses literally anyone who wants to be part of it.

Now, if we could just get Christians to consistently make great movies, we’d be all set.

I could have written this posting myself. Especially the MOVIES part.