Here’s another sample chapter of my forthcoming book for y’all to enjoy.

As many of you know, a few months ago, I sent a proposal for an astronomy-themed devotional off to a publisher, and it was enthusiastically accepted. But as the editors pointed out, it’s actually not quite a devotional. We’re not even sure how to describe it as at this point. But I’m going full-on Carl-Sagan-contemplating-the-universe with it. Only, you know, from a Christian perspective.

I’ll occasionally drop chapters here as I complete them so y’all remember I’m writing this thing. I plan to have the manuscript sent to the publisher by late spring of next year, and it’s scheduled to be released in January of 2026. We don’t have a title for it yet, but I’ll let y’all know once we settle on something.

This most beautiful system of the Sun, Planets and Comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful being. – Isaac Newton

We sense on every level that both beauty and order go hand in hand with purpose. Beholding a great work of art, whether a fine painting or an Italian sports car, causes us to think as much about the mind that conceived it and the hands that made it as of the thing itself. True enthusiasts are not merely content to admire the expressions in da Vinci’s The Last Supper or the lines of a 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO. They will tell you, rapturously, all you want to know about the lives of their creators and the impetus to produce such magnificent works.

Of course, no one would look at a great painting or a fine car and propose that they were accidental accumulations of paint or car parts. It would be absurd to do so. Nor would anyone suggest that they had been casually thrown together without much thought. That would be nearly as absurd. We know that in the human world great beauty and high order give every indication of a mind filled with intent. The greater the beauty and the higher the order, the more intelligent, skilled, and resourceful the possessor of the mind.

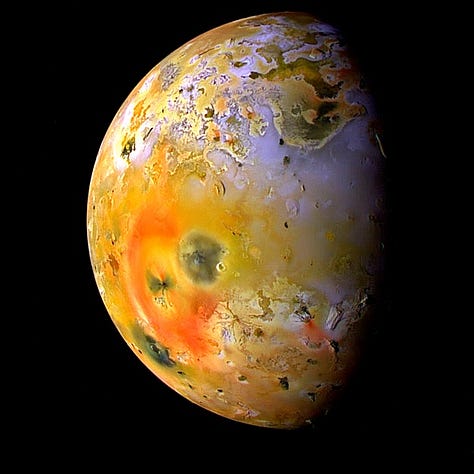

In Newton’s time, little was known of the heavens beyond the Solar System and the neighborhood of stars we inhabit. Indeed, it was assumed that the Milky Way was the only galaxy in existence, and that there was likely not much beyond what could be seen in the sky. With a rudimentary telescope, a skilled astronomer would have been able to see some details on the Moon and the five other planets then known to exist. Tiny Mercury would have been seen to cross the face of the Sun while Venus’ gauzy atmosphere would have protected the secrets of her surface. Jupiter’s distinctive atmospheric bands and iconic red storm would have been apparent, as well as Saturn’s magnificent ring system. Moons orbiting these gas giants would have appeared as tiny bright vassals following their planetary lords wherever they went. Astronomers would have spied Mars’ massive shield volcano, Olympus Mons, hints of its wintery polar ice caps, and its gargantuan canyon, Valles Marineris, brazenly dashed across its red face. But that—along with the Sun and a few dozen objects of indeterminate shape—seemed to be all that existed in the heavens.

As the field of astronomy matured during the Scientific Revolution, astronomers increasingly sought to flex their observational muscles by discovering comets. These celestial visitors had been known to mankind for centuries—Halley’s Comet may have been observed by ancient Greeks as early as the 5th century B.C.—and they captured the imaginations of 18th century people who, thanks to the widespread use of telescopes, were newly alive to the mysteries of the heavens. One of the chief mysteries at the time was the nature and origin of comets. We now know that comets hail from the dark and frigid outermost region of our Solar System, where billions of similarly icy objects tumble in their distant orbits around the Sun. But to the Enlightenment man, these occasional sojourners with their bright nuclei and long, streaming tails sailing through our inner Solar System were an irresistible enigma.

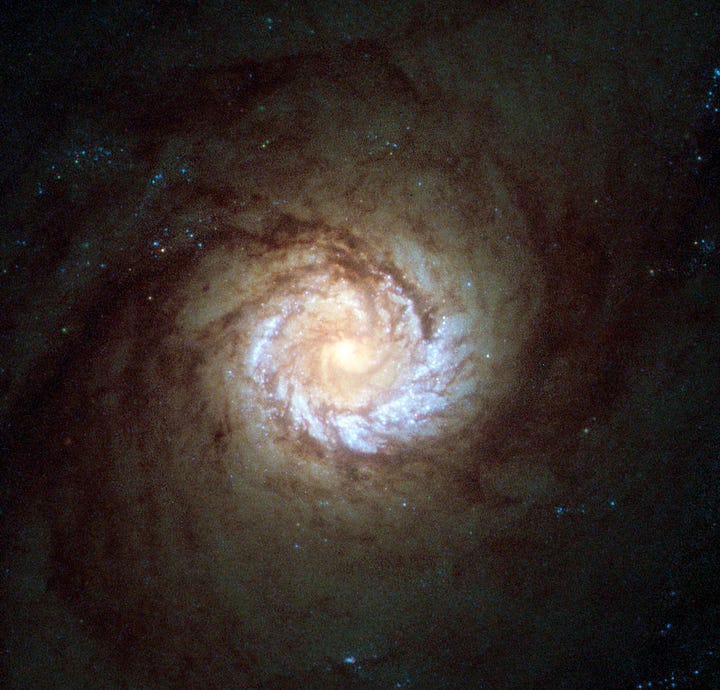

So keen were astronomers to lay claim to these objects, that French astronomer Charles Messier devised a catalog of indistinct objects masquerading as comets so that astronomers could ignore them. The only difference between these fuzzy imposters and genuine comets was that the imposters, unlike their transient counterparts, appeared fixed among the distant stars. Messier, undoubtedly satisfied with his work, had no inkling of the true significance of his catalog. As the fervor of comet hunting eventually waned, astronomers began to study the nebulae in his collection of nuisance objects, including several that were intriguingly spiral in shape. Nearly a century and a half after Messier published his catalog, astronomers shook the world with their announcement that many of its constituents were, in fact, distant galaxies. The Milky Way was not alone after all.

To a 21st century enthusiast of astronomy, the night sky is a cornucopia producing endless wonders. But we are now part of a world that is mostly accustomed to images of volcanoes and geysers on Jupiter’s moons, vast molecular clouds giving rise to a new generation of stars, and entire galaxies wheeling towards one another on billions-year-long collision courses. These scenes are as much a part of our everyday lives as paintings of serene landscapes were to the middle-classes of Newton’s century.

I cannot help but wonder what Newton might have remarked had he known that many of the ersatz comets of his time were entire galaxies or if he had been privileged to see the images of the universe we have today. To Newton, what little he knew of the universe, which was confined to our relatively small region of the Milky Way, was already sufficiently beautiful to impress upon him the wisdom and power of its Creator. And Newton’s universe is still impressively beautiful hundreds of years later. I have seen people, inured to the images they see on their screens, look at the rings of Saturn or the mountains on the Moon for the first time through a telescope and gasp in amazement.

No doubt Newton was similarly inspired by the visual wonder of the heavens when he remarked on the “beautiful system” we inhabit. Yet the truth is that the beauty he beheld in the universe pertained not so much to its visible attributes as to its mathematical order. Newton was, after all, primarily a mathematician.

Newton changed the world forever with his formulation of the universal law of gravitation. This closing bookend to the Scientific Revolution was built upon Johannes Kepler’s exquisitely precise mathematical model of the Solar System, a model over which Kepler had labored intently, guided by the principle that God is perfect. Newton, in the appendix to his great work, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, was guided by two additional principles: that God is wise and that he is Lord. Newton devoted the final pages of his Principia to marvel at the way in which God constructed the Solar System. He noted in particular that the eccentric orbits of comets ensures that, even as they pass through the orbits of the planets, they do not interfere with them. He could not imagine the beauty of this arrangement proceeding from anything other than a transcendent intelligence and power. He inferred that while the planets and comets “may persevere in their orbits by the mere laws of gravity,” that is not how they got there.

Unlike Albert Einstein, who would broaden the scope of Newton’s formulation of gravity in the 20th century, Newton did not believe in a God who was the “soul of the world.” Rather, Newton’s God is beyond his creation as “Lord over all,” a true God with true dominion over the world. Newton further posited that the diversity of phenomena he observed in nature could only have come from “the ideas and will of a Being necessarily existing.” Since he believed that all of this (and more) follows logically from careful observation of nature, he decreed, quite contrary to the spirit of our current age, that it is entirely appropriate to include discussions of God in the realm of science.

For believing scientists—and even for some unbelieving scientists—it is impossible not to invite God into the discussion. That is because great beauty and high order, particularly when expressed through the symbolic brushstrokes of mathematics on the canvas of the universe, bear the signature of a Being who willed it all into existence.

The heavens declare the glory of God,

and the sky above proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours out speech,

and night to night reveals knowledge.

There is no speech, nor are there words,

whose voice is not heard.

Their voice goes out through all the earth,

and their words to the end of the world.

—Psalm 19:1-4

Thank you for these stunning images of creative / created beauty. As well as for the excellent introduction into Newton’s understanding and insight into “the ideas and will of a Being necessarily existing.”

Looking forward to the launch of your ‘devotional’. W.

"... brushstrokes of mathematics on the canvas of the universe ..." Exactly.